The Early Years

Sentimental and nostalgic excerpts from a paper written by a student of the RCA while working for Zeev Aram in the late Seventies

In the run up to Natalie Gibson’s show in our gallery last year, we were fortunate to reconnect with Norman Chang who worked for Zeev Aram in the late Seventies. As a wonderful surprise, Mr Chang sent us a critical paper that he had written as a student of the RCA’s School of Environmental Design in 1977.

Titled ‘The revival of the Modern Movement in Furniture’, the paper fondly recalls the early years of Aram, then known as Aram Designs Limited: from Zeev’s studies at the Central School of Art and Design and his love of European trade fairs, to the opening of his very first showroom on the Kings Road in 1964 - and beyond.

Touched by Mr Chang’s recollection, we thought we would share some of the most sentimental and nostalgic excerpts from the paper - we hope you enjoy reading them as much as we did!

‘When you first meet Zeev Aram, it is from the other side of an almost choking cloud of his pipe smoke through which you have glimpses of a very relaxed character who seems removed from his profession; he could be taken for a doctor or physicist […]. He shoots up to greet you […] and beckons you to sit down, the smoke has hardly disappeared when out comes a new cloud, and only when that has gone do you talk business.’

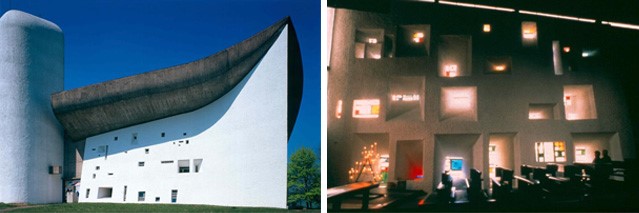

‘Starting comparatively late in his studies, he had spent the previous eight and a half years in the Israeli Armed Force, first in the Army following the declaration of the state of Israel and then in the Navy, which he regards as being the fundamental cause of his discipline and pluck. In spite of his naval experience and maturity, his first year at college was a period of […] not quite knowing where he was going. He finally allowed himself some direction when he went on a tour of Europe in 1959, and in Vienna first saw the works of Adolf Loos, a heartening experience in itself that was to be further overturned by a visit to Le Corbusier’s Chapel at Ronchamp*, from which he emerged “…completely dazed…and knocked out.., you know, this Le Corbusier, he know’s what he’s about…” And so it was an almost transformed Zeev who went to all the trade fairs he could manage to satisfy a hunger and cultivate an awareness of all aspects of current and past design.’

Left: Exterior view of Chappelle Notre-Dame-du-Haut, Ronchamp. Photographer: Paul Kozlowski. Right: Interior view of Chappelle Notre-Dame-du-Haut, Ronchamp. Photographer: Paul Kozlowski.

Left: Le Corbusier’s sketch of Chapelle Notre-Dame-du-Haut, Ronchamp, 1950-1955. Image courtesy of Fondation Le Corbusier / ADAGP. Right: Detail of coloured glass window. Photographer: Paul Kozlowski.

*Chapelle Notre-Dame-du-Haut, Ronchamp, was designed by Le Corbusier between 1950 and 1955. Laid out according to the Modular principle, a curvilinear shell of two concrete membranes constitutes the roof of the building. Resting atop short struts which form the vertical concrete walls that follow (in plan) the form of the roof, a gap of a few centimetres allows for a slither of daylight to enter the building between the roof and the walls. The main source of daylight, however, enters through a pattern of deep openings with clear and, in other places, coloured glass. Furnished with benches of African wood created by Savina and a cast iron communion bench made by the Foundries of the Lure, the cement paving and white Bourgogne stone of the chapel floor follows the natural slope of the hill towards the altar. Adjoining the main structure, towers of white-washed stone masonry and cement domes lend verticality to the chapel, which was recognized as a World Heritage Site in 2016.

‘Because of his reluctance to fall in with the whimsy, [Zeev] looked to the Twenties for inspiration, by opening a showroom for Modern Movement furniture. Much of it, even in 1964, was nearly forty years old, yet the natural process of design aging had not touched any of the pieces. They are true classics, still acceptable today and will probably remain as for at least a further thirty years.

'What of Mr Aram…? That inspiration had first manifested itself to him at the end of his first year as a student, then everything was Corbusier and the Bauhaus, often spending his lunch-hour at the London Art Bookshop.

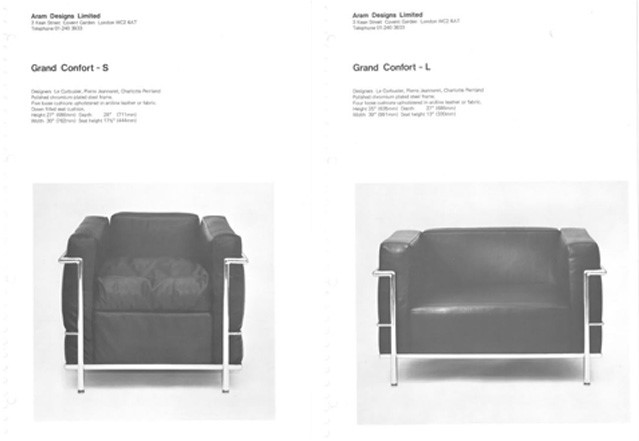

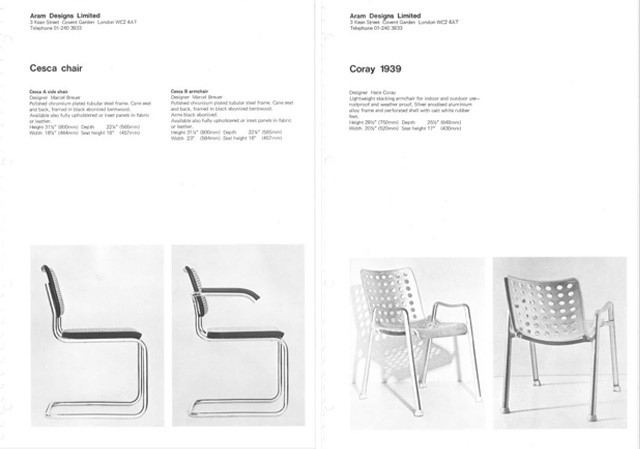

‘From the Corbusier/Jeanneret/Perriand Grand Comfort*, to Marcel Breuer’s Cesca* and the Hans Coray Chair*. Having originated from the Modern Movement, very few people [in the United Kingdom] were aware of such furniture, and even only a few architects and designers with ‘modernist tendencies’ knew of them.’

Left: 2 Fauteuil Grand Confort - Petit Modele. Image courtesy of Zeev Aram’s archives. Right: Fauteuil Grand Confort - Grand Modele. Image courtesy of Zeev Aram’s archives. Both from the Cassina i Maestri Collection Le Corbusier/ Pierre Jeanneret / Charlotte Perriand.

*Designed In 1928, the 2 Fauteuil Grand Confort - Petit Modele and 3 Fauteuil Grand Confort - Grand Modele Armchairs by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand describe two sizes of polished chrome coated steel frame and five loose cushions filled with feather down upholstered in aniline leather or fabric. Today, the Grand Confort is available in a chrome coated or semi-matt enamelled steel frame, a polyurethane core with feather or polyester filling, and a selection of new colourways introduced in celebration of the 50th anniversary of their production by Cassina in 2015.

Left: Cesca Chair by Marcel Breuer, 1928. Image courtesy of Zeev Aram’s archives. Right: Landi Chair by Hans Coray, 1939. Image courtesy of Zeev Aram’s archives.

*Also designed in 1928, the Cesca Chair by Marcel Breuer describes a chromed steel cantilever frame and lacquered frame with woven cane backrest and seat. Developed some time later in 1939, the Landi Chair by Hans Coray describes a lightweight, stackable chair with ninety-one holes that punctuate a moulded seat shell in silver anodised aluminium (of which its frame is also made), ensuring its modest weight, flexibility and trademark appearance.

’57 Kings Road in 1963-1964 was then an old coffee house and restaurant, and it was here that he decided to open a showroom for Bauhaus furniture, giving their designers and their movement some representation in the United Kingdom.

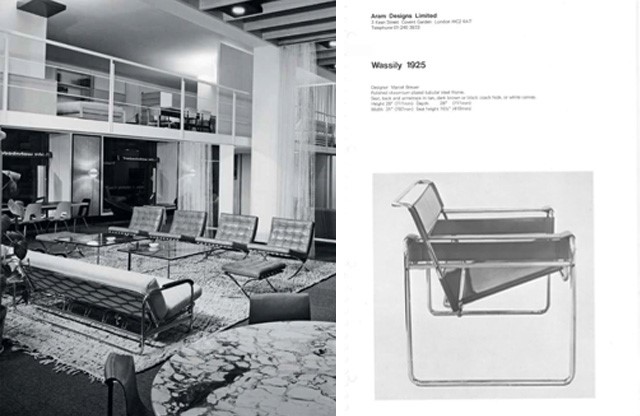

'The showroom, when completed, would become a descendant of the Wohnbedarf Furniture Store* in Zurich in 1933, that had the same aspirations as its British counterpart. At the time of the construction of the showroom, there were no rock punk bands, no boutiques, no anti-establishment fervour, and no furniture. So in January 1964 Mr Aram went over to the Cologne Furniture Fair to select items. For four days with a friend, he travelled the stands ticking off those furniture he thought might help him. He had no idea as to how he could place orders or even obtain trade literature, he was [so] totally inexperienced that he eventually left emptyhanded. But he had seen the Wassily* which was then being manufactured under licence from Marcel Breuer in Italy.’

Left: Wohnbedarf showroom in Zurich, 1959. Photographer unknown. Right: Wassily Chair by Marcel Breuer, 1925. Image courtesy of Zeev Aram’s archives.

*Founded by Sigfried Giedion, Werner Max Moser, and Rudolf Graber in 1931, Wohnbedarf (formerly Wobag), presented furniture collections and exhibitions at its showroom, featuring tubular steel designs by Swiss architects Max Ernst Haefeli, Wilhelm Kienzle, Werner Max Moser, and Flora and Rudolf Steiger, as well as pieces by Marcel Breuer, Alvar Aalto and Le Corbusier / Pierre Jeanneret / Charlotte Perriand. Moving to Zurich, and a new showroom designed by Marcel Breuer and Robert Winkler, in1933, Rudolf Graber and his mother took over the company.

*Designed while he was still apprenticed at the Bauhaus in 1925, the Wassily Chair by Marcel Breuer took its inspiration from the tubular steel frame of his first bicycle. Making a duplicate of the prototype for his fellow alumnus, Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky, the design was affectionately dubbed the Wassily Chair by Italian manufacturer Dino Gavina.

‘After the return flight home, Mr Aram contacted the manufacturers asking if they would accept an order and at the same time asked if there were any other furniture available. As there was no Modern Movement furniture obtainable in Britain there was some hesitation on the licence-holder, [Dino Gavina] to confirm the order, which he eventually managed to have accepted along with quantities of Cesca, Laccio*, Grand Comfort, and the Chaise Longue*.’

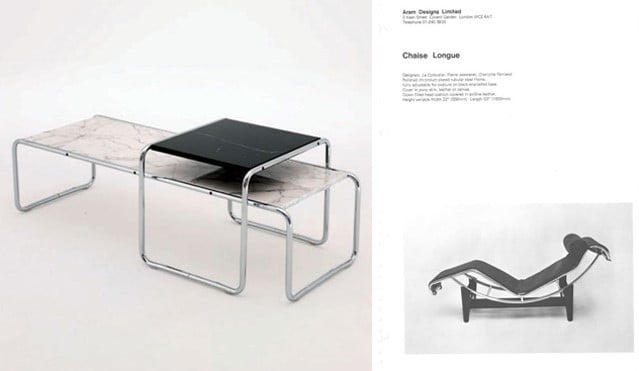

Left: Laccio Low Tables by Marcel Breuer, 1925. Image courtesy of Knoll International. Right: 4 Chaise Longue by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand, 1928. Image courtesy of Zeev Aram’s archives.

*Also designed by Marcel Breuer in 1925, the Laccio Low Table Short and Laccio Low Table Long were conceived as a companion for the Wassily Chair. Also utilising tubular steel in a polished chrome finish, the table top was made from a smooth plastic laminate in a black, white or red satin finish (with more luxurious marble finishes having since added). Meanwhile, the 4 Chaise Longue was designed alongside the 2 Fauteuil Grand Confort - Petit Modele and 3 Fauteuil Grand Confort - Grand Modele by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand in 1928. Produced by Cassina since 1965, it is finished in a range of leathers, ecru canvas and ‘hairyskin’.

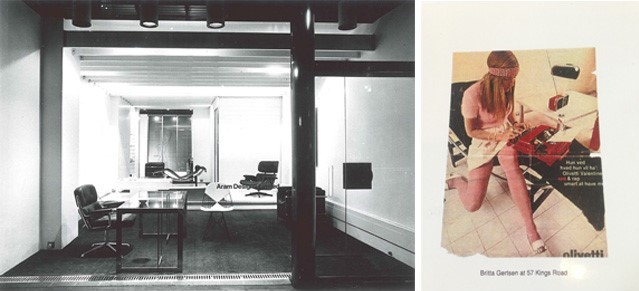

Left: Aram Designs Limited showroom at 57 Kings Road, Chelsea, 1964. Right: An Olivetti advert featuring Britta Gertsen, Zeev Aram’s Altra Table and other designs sold at 57 King’s Road. Photographer: Tim Street-Porter.

‘The Aram Designs showroom opened in April 1964, a day early for a press reception. Hardly anyone turned up. On the official day, it was the same. There were some misgivings and it was discussed as to some of the reasons for such non-attendance. But later in the day [the Vogue] photographer, Claude [Virgin]*, bought a Wassily and on declining to have it wrapped walked down the Kings Road with the Wassily neatly balanced over his shoulders.

'The days following the opening it soon became clear that they were receiving a mixed reception. Some were saying very uncomplimentary, negative things…”why is he selling old furniture…” and the like. Then came along the appreciation […]. Architectural Association and Regent Street Polytechnic students almost formed a queue, and many were given furniture on hire-purchase.

'It was appearing to be a success.’

*Claude Virgin (1928-2006), was an American-born fashion photographer who accepted an invitation to work at British Vogue in 1957. Fully embracing British culture and style, he rented a studio off Kings Road, where he became friends with the likes of Mary Quant, who founded her Chelsea Bazaar boutique in 1955, and Terence Conran, with his new Design Group. As Vogue’s most in-demand photographer of the Fifties and Sixties, Virgin was a formative influence on several photographers, not least Helmut Newton, who wrote: 'His photographs were sexy and different from anything seen before in England.'

‘Aram Designs’ specific aim was to bring into the United Kingdom internationally known designs which were not previously available. For two years after the opening they were still receiving comments associating the furniture with hospitals, the clinical coldness of tubular steel which [was] exactly what people had said forty years before.

'Years later there was another turnabout in attitudes. The Modern Movement furniture was now comfortable, practical and well designed, with a kind of hygienic elegance. “Lightness and precision, of form, of chromium plate to leather, were the spiritual expressions of intense simplicity and beauty…”’

And just as Mr Chang’s paper suggested back in 1977, the designs that Zeev Aram introduced to the United Kingdom in the Sixties remain ‘true classics’ to this day - even surpassing his prediction that they would be sought after for ‘at least a further thirty years’.