Villa E-1027 restored at last

A tribute to furniture as architectural agent

In the first week of May, the team at Aram travelled to Roquebrune-Cap-Martin for a private tour of the newly-restored Villa E-1027. Designed by Eileen Gray — the twentieth-century furniture designer who entrusted Zeev Aram with the worldwide licence for her designs before her death in 1976 — this trip held special significance to the team who, over the years, have provided furniture and support to the restoration project.

Mirroring the meticulous restoration of the Villa, the reconstruction of the original furniture by Association Cap Moderne — who worked with makers from all over Europe — is a beautiful tribute to the importance of furniture as an agent of architecture.

A Complicated History

Born in 1878 to a wealthy family, Eileen Gray lived between Ireland and London before studying Art at the Slade School. After graduating, she learnt the craft of lacquering from Japanese master, Seizo Sugawara, and in 1907, she began designing furniture in Paris. Though these early works championed the Art Deco movement, carved wood and lacquered finishes, by the mid 1920’s her focus shifted to the De Stijl movement, sleek lines in chrome and glass.

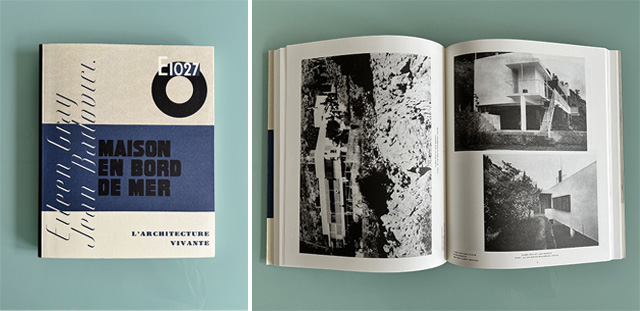

L’Architecture Vivante - Maison en Bord de Mer

By this time, Gray had become involved with Jean Badovici, a Romanian-born architect and the editor of L’Architecture Vivante, for whom she had begun to envisage a Villa on the Riviera where the two could live and work peacefully together. Under Badovici’s influence, this evolved into a place to entertain their friends. While looking for somwhere to build, Gray – a self-taught and first-time architect – happened upon a bit of land at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin which was part of a terraced lemon grove.

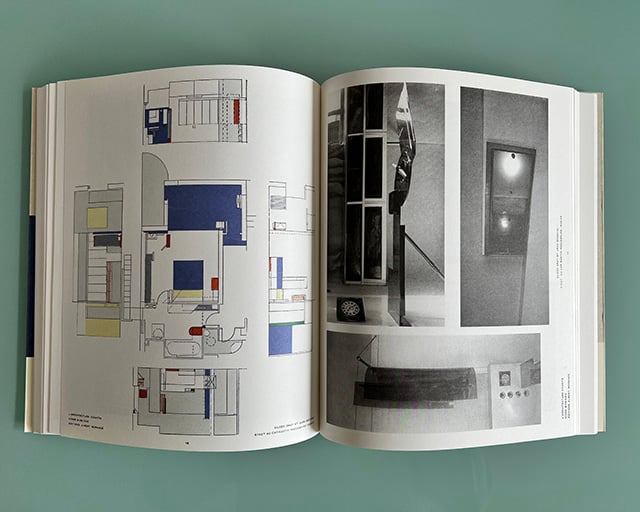

Between 1926 and 1929, Gray worked with Badovici on architectural plans and designed furniture to ‘blend into the architectural whole’. She also had a few items of furniture and rugs sent from Jean Désert, her Parisian gallery. By 1929, the year of the Villa’s completion, there was an inventory of 180 items of furniture, lamps, rugs, fittings and accessories.

The Villa, which was named E-1027 in an entwining of their names (E for Eileen, 10 for the J of Jean, 2 for the B of Badovici, and 7 for the G of Gray), was an encoded display of the warmth that Gray would bring to modernism. For Gray, E-1027 was not a machine for living – it was to be a home.

In 1929, Gray moved in with Badovici. That same year, a special issue of L’Architecture Vivante – Maison en bord de mer – was devoted to the Villa in which a conversation between Gray and Badovici on the return to basic elements, pathos and primordial emotions was published. The creative partners visited the Villa regularly between 1929 and 1931, after which they fell out and – having bought the house as a gift for Badovici – Gray left, moving to Menton to work on 'a house of her own'.

Left: Le Corbusier, photograph by Lucien Hervé. Right: Les Unités de Camping

Up until his death in 1956, Badovici both used the house himself and leant it out to friends, of which Le Corbusier was one. In 1937, 1938 and 1939 – long after Gray had left — Le Corbusier visited Villa E-1027. It was in 1938 that he first painted two Picasso-style murals in the Villa and, encouraged by Jean Badovici, returned the following year to paint another five – in what has been described as 'a bizarre act of vandalism with psychological undertones'. He later returned to restore several of the murals which were damaged during War II, and even built Le Cabanon – the only building he ever designed for himself – and Les Unités de Camping on the hillside just above the site which he visited often. In 1960, Villa E-1027 was sold to Madam Schelbert – an aristocratic friend of Le Corbusier who had orchestrated the sale himself in order to continue imposing his influence over the Villa. Though she kept the interior intact until Le Corbusier’s death in 1965, she later began to make substantial modifications and alterations, destroying a number of fixed and mobile pieces of furniture.

In 1974, her psychiatrist bought the Villa under suspicious circumstances (though she continued to occupy the home until her death in 1982). Her heirs contested Dr Kaegi’s ownership, but lost the case in 1990 and in 1991 he sold the twenty-two surviving pieces of mobile furniture at a Sotheby’s auction — much of which has now been acquired by the Centre Pompidou, the National Museum of Ireland and the V&A. The Villa soon fell into disrepair becoming inhabited by squatters who, in 1996, murdered Dr Kaegi.

A Meticulous Restoration

In 1999, the municipality of Roquebrune-Cap-Martin engaged the services of Renaud Barres — a young architect whose diploma thesis was to be the Villa’s restoration. Later that year, the Villa was purchased by Conservatoire du Littoral with the help of the municipality and, in 2000, it acquired landmark status. Remaining on site until 2004, Barres carried out thorough archaeological inventories of the house, garden and items dispersed by the Monaco auctions.

A first restoration campaign was then carried out between 2004 and 2012. However, in 2014, Association Cap Moderne was charged with restoring the building — and its furniture — to its 1929 state. This base year was chosen by the Technical Committee as ‘the moment best preserved by archival and photographic record’.

Claudia Devaux, a heritage architect, was chosen to carry out the new restoration of the architecture, while Renaud Barres and Burkhardt Rukschcio were commissioned to carry out the reconstruction of the fixed and mobile furniture. The 2021 completion of the restoration was accompanied by the assembly of an exhibition at Gare d’Menton titled E-1027, Furniture as Architectural Agent which explores in depth how the architects and makers worked to reconstruct the original furniture, fittings and interior in exacting detail.

A Private Tour Lead by Michael Likierman

"As you see, the entrance is absolutely not grand – it’s tucked away over there – and we’re going to have to go down several steps in order to get to it" begins Michael Likierman, President of Association Cap Moderne. He has been generous enough to take us on the private tour himself.

As we look down at Villa E-1027 – a white, modernist structure resting on pilotis that is reminiscent of an ocean liner – Likierman notes that it is neither parallel to the terraces nor to the sea. What Gray chose for the position of the Villa was to be on a solar axis. "If you look at the document that she created in that time, she looked for where the sun rose and where the sun set, and where the wind came from and so on. She positioned the house so as to have sunrise to sunset, to have the prevailing wind, in a particular way. So it’s sort of skew on the terraces, neither parallel to one nor the other". Describing this as "slightly disorientating", Likierman explores, "it’s a small space, but what [Gray]’s going to do is make you not quite sure where you are and that’s going to make you much more receptive to what’s going on around you".

As we approach, Likierman starts to point out interesting features, including the vernacular shutters. "She was not an architect so she came to problems in a very fresh way. For example, the question of air circulation and light. These are the shutters which you can slide so that you can have the whole thing clear, so that there’s lots of light, or you can have them back here" — Likierman asks a member of the team, "Do you think you could just lean over and give those a little push?" before continuing — "or you could have them half-open, half-closed".

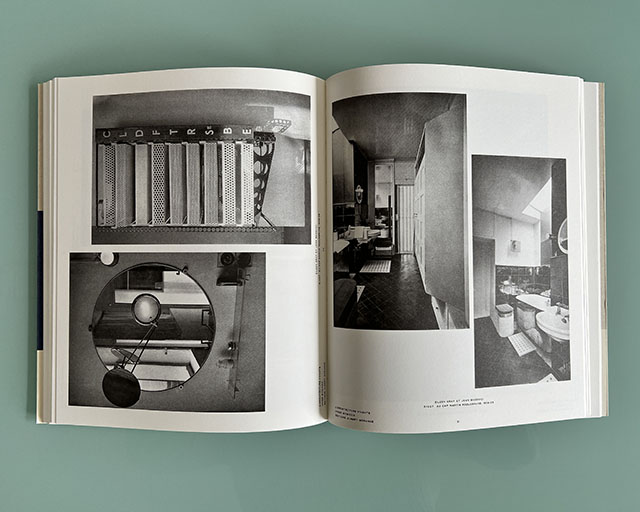

We eventually arrive at a wide, covered entrance and are greeted by a triptych of features that reflect Gray’s attention to detail: an adapted Hermès saddlebag letterbox, a filament night light with smoked glass, and a point de diamond glass window which Likierman describes as "an amusing example of reverse industrialisation — it’s amusing because this was an industrial, cheap glass at the time and for us to remake it, it is extraordinarily complex and expensive". On the front-facing wall, a 1938 mural by Le Corbusier is juxtaposed by Gray’s discrete stencilled labels. To the left it reads sens interdit – no entry – leading towards the service area – a Summer kitchen with coal burning stove and Pailla wall lamps rewired with ceramic bobs as they would have been in 1929; an outdoor Winter kitchen; and a spiral staircase that leads down to the lower ground floor servants’ quarters.

To the right it reads entrez lentement – come in slowly. "She liked discovering things slowly", says Likierman as we turn right and are guided by an arrangement of polychromatic cubbies until the large room finally reveals itself. A picture window designed on a concertina principle – a patent of Badovici’s – boasts postcard-esque views of the Riviera. E-1027 represents the first Villa in which this wide expanse of concertinaed glass could be pushed right back, blurring the boundary between the interior and the south-west facing terrace. Nautical canvas shades, expertly reconstructed by the University of Vienna, frame the view. Likierman adds with a touch of humour: "You should of course have some evening sun pouring in from there, one of the great reasons for visiting at this time". Today, it seems, is the only day from May to August that it is overcast in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin.

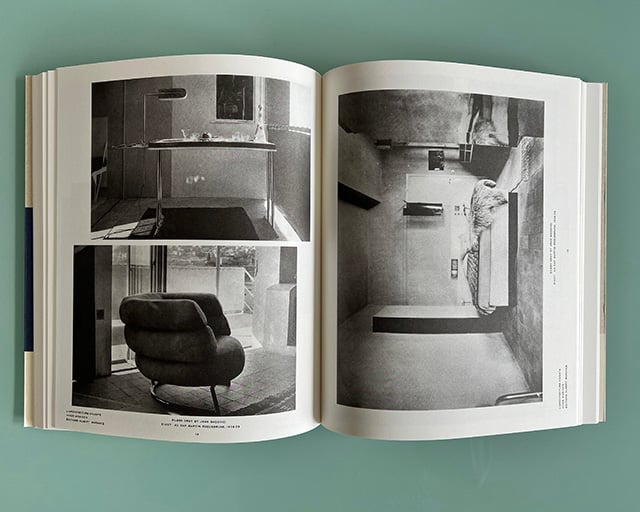

In front of the picture window sits a Bibendum chair: "It’s not the Bibendum you know exactly. It’s the Bibendum that was here in 1929. It’s a reconstruction of a prototype from both the drawings and the photographs. You will see that it’s not leather, for example, but oil cloth and that the proportions are slightly different than that you know".

In turn, Likierman focuses our attention to the left – where there is a dining area with a beautiful nickelled tubular steel and cork-topped table, an alcove that transforms into a bar for making lemon Helga gin and tonics, and diffuse point de diamond lights – and then to the right – where there is a cosy living area equipped with a large cushioned divan ("a sofa to them in those days") set against a low wall, deep pile rugs, and a fireplace with the flue going up which they would have sat around in the Winter to light a fire with the sea behind. The low wall behind the divan is the only example where the Association Cap Moderne screened a Le Corbusier mural to preserve the integrity of Gray’s vision. Though one of Le Corbusier’s more prominent murals, the "violent" painting destroyed the harmony of the space, resulting in what Likierman describes as "one of the great fights we had with the historic monument". Instead, a reconstruction of a hand-drawn Maritime poster on tracing paper attached to the wall with drawing pins evokes Gray’s more subtle daydreams of far-away journeys and the Caribbean.

Also in the living room is an E-1027 table and a black leather Transat chair: "You will see a table that we all call the E-1027 Table that I believe you know. That has not got a glass top on it, but a celluloid top. If you touch it, it quivers in the usual way that celluloid quivers. In 1929 there was no glass topped E-1027 table, these were the prototypes (or recreations of them)". Conversely, a reconstruction of the final prototype of the Transat Chair from 1929 has not yet arrived at the Villa: "It’s being made at the moment in Austria and will be here shortly, but in the meantime – thanks to Daniel [Aram] – we have this Transat to look at".

Further to the right the room transitions into a sleeping alcove or niche with a siesta daybed equipped with a day light, a night light, a mosquito net that comes out and goes over the bed, and an "infinitely adjustable" pivoting reading table with a book perched on it: "This is the book that was in the photograph, open at the page in the photograph". Facing it is a partitioned shower area with a celluloid curtain and straight ahead, a double door that can be opened to let a light breeze through that leads onto a small balcony with a hammock beneath a cement canopy.

Returning to the bar which folds back onto the wall, Likierman leads us into the master bedroom – a boudoir-studio with private terrace, which Likierman describes as "a sort of miracle". An early attempt to get diffused lighting in polished glass hovers above a white drafting and a writing table. Though no originals survived, Association Cap Moderne had two of these tables remade. One for here, and another for the National Museum of Ireland. We turn to the left to reveal a bed layered with ribbed textiles and an Afghan fur, a polished aluminium and cork dresser – Likierman’s favourite piece in the house which he describes as "probably the most beautiful piece of furniture which [Eileen Gray] ever made" — and an adapted dentist’s chair. The master bedroom then leads out towards a bathroom with glazed black tiles and a bath tub covered in aluminium sheeting to provide interesting reflections. A staircase then leads us down to the lower ground floor where the guest room and servants’ quarters continue the use of layered textiles and polychromatic walls.

An outdoor living space opens up to the south-west garden which is sheltered by maritime pines in an extension of the intimacy of the Villa. Arrangements of paved pathways and benches provide various places of ambience in which to sit, culminating in a solarium. The terracotta, black and white tiles form a 'stone couch' angled towards the sun and a table for cocktails. Sited on the lower limits of the terraces, the land quickly falls away and a small stair provides access directly to the sea.

We also had the pleasure of visiting the following cultural establishments which we would like to recommend to guests of the region:

Guided tours on the site of Villa E-1027: Thomas Rebutato’s L’Etoile de Mer and Le Courbusier’s Le Cabanon and Les Unites de Camping

La Foundation Maeght: www.fondation-maeght.com

La Colombe D’Or, St Paul de Vence: www.la-colombe-dor.com