Aram + Ally Capellino

A shoot in Devon threw Grace our creative manager and Ally, creative director of Ally Capellino, together into the same train carriage. The idea developed to make a comparison between the qualities and value of classic modern furniture, and a good bag. A year later we have asked a set of four creatives to tell us their thoughts on classic design. The photos are taken here at Aram on Drury Lane by Sarah Bates.

Classic Cuts Part Four: Marcus James

For the fourth and final instalment of our Aram + Ally Capellino Classic Cuts series, we met with artist Marcus James. Marcus, whose classical fine art training was based around life drawing and nudes, spoke to us about his work and how the logical and mathematical order of classicism remains prominent in contemporary art.

Marcus James with the Cherner Bar Stool, Gubi Semi Pendant, and Hoy Leather Backpack

Aram + Ally Capellino: What does the word ‘classic’ mean to you within your world as an artist?

Marcus: I think, for me, it’s more the concept of timelessness which is important. Something which is relevant now, but which is also going to be relevant in a long period of time as well. In my practice, classicism has definitely played a part - not necessarily in terms of where the origins have come from, in the Greek or Roman sense of classicism, or in how it looks aesthetically, but more so in the logical and mathematical order which translates into my work. I guess it’s the second wave of classicism - Neoclassicism - which is relevant to my work.

A + AC: Who or what are your ultimate ‘classic’ artists, movements or works of art?

Marcus: They’re not very obvious ones, in a way, because I’m quite a fan of Le Corbusier who drew a lot from classicism and the Golden Ratio in modernist architecture. I mean, obviously there are certain parts of him which I’m not very into, but I have been quite a fan of his architecture in Paris and Marseilles. During my education, I also got into early Picasso which, again, is more so Neoclassicism. And then there are Henry Moore’s early sculptures which make reference to reclining nudes. He did a series on people lying down in tube tunnels during the Blitz and relating that back to similar reclining poses of Greek statues, which I was quite interested in - less the normal route of classicism.

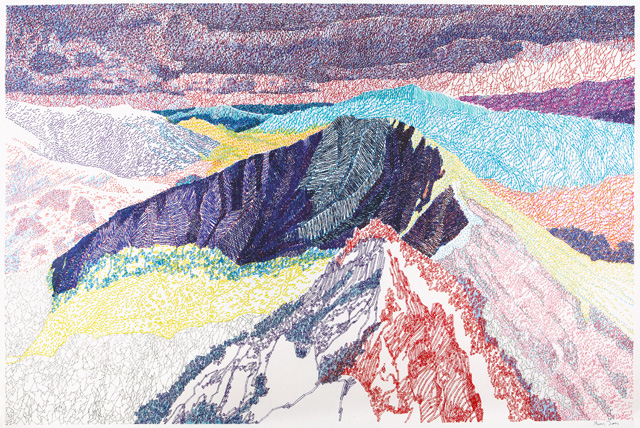

Crib Goch by Marcus James

A + AC: You’ve had a ‘classical’ fine art training. How much does it continue to be an influence and how much do you feel you have departed from it?

Marcus: Most of my classical training was based around life drawing and nudes. I spent a year doing anatomy drawing at University College Hospital in the morgue and that really did influence me quite a lot. If you were to look at my work now, you might not be able to tell necessarily, but it was the foundation at the time - definitely! It played a big part.

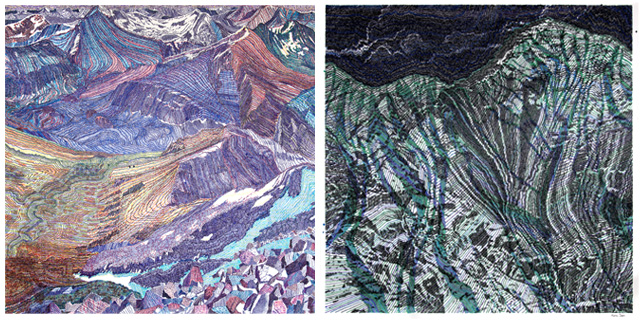

Ben Nevis (left) and Carantoohill Dark (right) by Marcus James

A + AC: What is the value of having a strong background knowledge of the ‘classics’ when pushing the boundaries of art?

Marcus: It gives you another language to use, in a way. I don’t think you necessarily have to have it, but it definitely broadens your ability to explore your ideas; you might never use it, but it can be important.

A + AC: Are there any ‘classic’ techniques, colours or materials that you continue to use within your contemporary practice?

Marcus: Yes. I think, again going back to the use of logic and mathematics in the order of my work, a lot of my drawings are based off of small marks that make up a bigger picture - almost a facsimile of nature which is what they were doing in the classics somewhat anyway. They were trying to see an order and a logic to things.

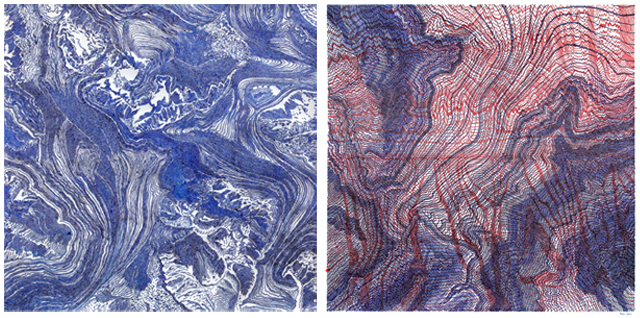

Siachen Glacier (left) and Bering Sea (right) by Marcus James

A + AC: What are your current researching and methods?

Marcus: Most of what I do is in response to my surroundings. I’ll see something and that will be the stimulus. At the moment, a lot of my research isn’t actually based on anything from the past - it’s a bit more forward looking, especially looking at different landscapes and the political discourses surrounding those landscapes.

Marcus James with the Cherner Bar Stool, Gubi Semi Pendant, and Hoy Leather Backpack

A + AC: Lastly, how do Ally Capellino and Aram tie in with your personal concept of ‘classic’?

Marcus: I definitely see both of them as having a timelessness, which links to the concept of classics - you can definitely see that it’s relevant. You can wear and use and sit on their pieces for years to come!

Classic Cuts Part Three: Marina Willer

For the third instalment of our Aram + Ally Capellino Classic Cuts series, we met with graphic designer and filmmaker Marina Willer. Marina, who is a partner at the illustrious, multidisciplinary design consultancy, Pentagram, spoke to us about her work and how she views modernism as the ‘classic’ of her lifetime.

Marina Willer with the Vitra Eames lounge chair and ottoman, Flos Arco floor lamp, and Lloyd Calvert Leather bucket bag

Aram + Ally Capellino: What does the word ‘classic’ mean to you within your world as a Pentagram partner, graphic designer and filmmaker?

Marina: A classic, to me, is something that is timeless, that is not being seduced by fashion or trends but has a more grounded view. It’s not so much about going with the flow as being able to stand back and have a perspective. I always think about classics in my lifetime as modernism and the belief that design, which is the discipline I operate in, can change things for the better - a certain notion of utopia, in a way. Postmodernism is the opposite of that. It’s nihilism, it’s when you start to not believe in anything, which is very easy to fall for in times like these.

A + AC: Who or what are your ultimate ‘classic’ designers, filmmakers or films?

Marina: I have always been interested in films which are less pretentious, less gimmicky. I think of The Godfather, how beautiful the story is and how it defined a certain way of making films which was followed by Hollywood. I also really like Iranian films because they give you time, perspective and space to think. You’re not seduced by the action and the overwhelming suite of effects that you see in cinema today. There is something that puts me off about the excess of gimmicks. So, in terms of films, I think those two examples would be my top choices for their pure simplicity and storytelling.

In terms of design, I think I’ve always been very inspired by modern designers and visionaries: László Moholy-Nagy, for example, or quite a few who came out of the Bauhaus. I think that a lot of the designers that came out of the Bauhaus inspired our generation and then there are new interpretations which are very special as well, such as Richard Rogers’ architecture. I have been very fortunate to have worked with him. He was an incredible visionary who was able to think about what modernism meant today and who believed in the societal role of architecture and design.

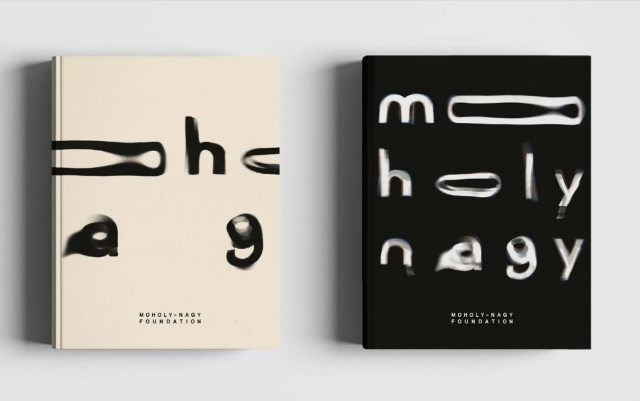

Brand identity for the Moholy-Nagy Foundation

A + AC: Your work bridges multiple fields. As such, do you find that there is a single, common thread that defines ‘classic’ across the board?

Marina: If I think about the classics in my lifetime, there is that belief in modernism. Not what didn’t work about modernism, which was the trying to over orchestrate life, but the aspects that did work which were quite radical. It was really about using design as a force for good and I think we are now more than ever in need of those beliefs. There are incredible ways to reinvent how we think about transportation and cities, the things that we consume and consumption in general, and the reshaping of those through design. All of these come from a classic perspective, which is a modernist way of seeing things, but with the perspective of today. Not a nostalgic, mid-century celebration of beautiful things, which we can all get seduced by, but the belief that we can change things for the better.

A + AC: That leads nicely into our next question which is how do you maintain the essence of ‘classic’ within an age of instant gratification?

Marina: It’s about creating space - space to think and space for the audience to read the stories in the way that they want to read them, not just to be bombarded and seduced by the sheer amount and dramaticity of effects. Again, what is beautiful about Iranian films (or the work of a director like Andrei Tarkovsky, who is completely different) is that they are all about giving space. I made one feature film in which I tried to talk about a subject that was very loaded, over exposed and explored, about how we got to such a bad place in humanity in terms of intolerance. My attempt with that film was to create a lot of space to think and a narrative that was very calm and contemplative, rather than imposing on or manipulating the audience to feel things with the bombardment of effects.

In design, for me, it is the same. I mentioned Moholy-Nagy as an incredible influence because he was really radical in his exploration of the crossover between disciplines: film and photography, sculpture, painting, illustration and graphics. He was very experimental, as well as purposeful, with a degree of purity. I sometimes turn my back to effects and the seduction of things that you can do with the digital world. In the end, what we create is shared digitally and that’s fine, but it doesn’t need to impose a certain style or aesthetic because there are many other ways we can experiment and which lead to much more unique outcomes - those which are more accidental, less controlled or replicable.

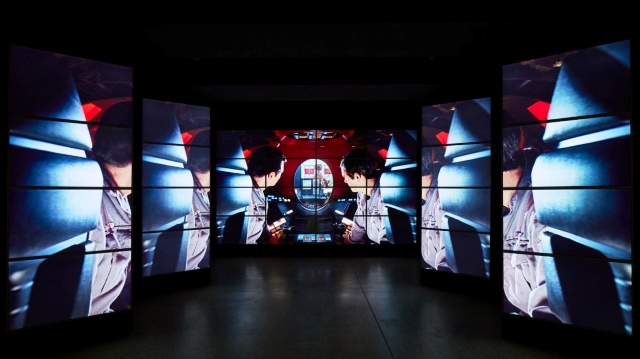

Three-dimensional design, exhibition graphics, identity design, marketing campaign and entrance film for Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition at the Design Museum with the support of William Russell Architects. Photographer: Ed Reeves

A + AC: What is the value of having a strong background knowledge of the ‘classics’ when pushing the boundaries of design?

Marina: I always think it’s important that we know why we’re choosing to use form in a certain way, for example when we designed an exhibition about Stanley Kubrick’s work (again, he is another director who I perceive as a classic in the sense that the films he made almost never age and are still as provocative as they were then). If you think about Space Odyssey, he directed that before we had been to the Moon, before we had been to space. He was trying to anticipate those things and the notion of the International Space Station. The design elements in that and all of his films were based on modernism.

Today, there are so many fashions that people just fall into the pressure of doing things like everybody else. I think having points of reference helps us to think about the meaning behind the decisions that we make, whether we are designing or drawing, painting or making a film. When you read a book, the way that the type is laid out influences how you understand and read it. Or in film, the way it is framed. Kubrick framed everything from a single point perspective that was really symmetric, he wanted to give control and perhaps the feeling of distance between the audience and the story. If you think of The Godfather films, the orchestration of decisions is based on a classic view, but there is a sense of time. Like you mentioned, today we are exposed to a rhythm and an accelerated way of reading. When you see a trilogy like The Godfather, it puts you in a different time and space because Francis Ford Coppola takes the time to tell the story.

A + AC: What are your current researching and methods?

Marina: The good thing about how we work at Pentagram is that we have several projects of a different nature at the same time. So, besides my own love for film, there is this combination of projects which each give me a different point of entrance. I am always doing projects for social and not-for-profit organisations and that also puts me in a place where I have to think about change. How can we transform society and create a language that feels as if it’s inviting people to participate, rather than a one-way language which imposes certain beliefs? And then there are always design and branding projects for organisations in arts and culture that pose the question of what our relationship with audiences should be and how we can create more participative systems of open dialogue, rather than what was perhaps much more part of the era of modernism which was this idea of the one-person genius. That is one of the aspects that I think has had to change. Today, it’s much more about collaboration and generating things together - it’s about collective origination of ideas, rather than solo practice.

Brand Identity for Tate Modern

A + AC: Does working with ‘classic’ institutions, and the stability they possess, allow a greater sense of freedom?

Marina: I’m a partner at a design studio which I think you could refer to as a classic. We’ve been around for fifty years and are very much a result of the utopian views of the Sixties, which were about transferring control from the companies to the designers. All of the partners, including myself, are creatives - we’re all designers and we all believe in the power of design. That position is quite privileged and I think it helps give us the freedom to explore and experiment, to attract projects and clients that come to us because they really want to work with a design studio that is so established, admired and recognised. In this sense, I see having a classic position, having earned it (I joined ten years ago as a partner but I’ve inherited this incredible platform), as a really lucky place to be.

For example, when I did the branding for Tate (not alone, but I was the designer leading the project and strategies and there was a team around me), that was an incredible opportunity to create something much more experimental because they had already been established in the field of art and they were questioning and rethinking the meaning of art. That position allows you the freedom to be provocative because you’re supposed to be leading the conversation. You’ve earned a place that gives you or even demands of you to be forward thinking - but in a way that is still classic, because the worst thing you could create for one of these very well respected organisations would be something that made people feel as though they are trying too hard or creating something frivolous that dumbed down the discussion on the subject that they lead. So, it’s important that we don’t just create something that is fashionable. For us, the responsibility is to create something that in ten, twenty, fifty years’ time might still be representing them accurately because it was done in a way that was unique to them and meaningful.

The Vitra Eames lounge chair and ottoman and Lloyd Calvert Leather bucket bag

A + AC: Lastly, how do Ally Capellino and Aram tie in with your personal concept of ‘classic’?

Marina: I’ve been a massive fan of both brands, Ally Capellino and Aram, for many years - I think because they value design and the meaning behind form, but also because they both stand for quality and things that last and things that are timeless. The amount of craftsmanship that you see in any object, whether something created by Ally Capellino or sold at Aram, is incredible. You know that they are made in a way that is robust, that is solid.

Classic Cuts Part Two: Max Radford

For the second instalment of our Aram + Ally Capellino Classic Cuts series, we met with London-based interior designer and gallerist Max Radford. Max, who runs The Radford Gallery, spoke to us about his work and gave us his thoughts on how a strong knowledge of the ‘classics’ helps when pushing the boundaries.

Max Radford with the Zanotta Maggiolina armchair, Lumina Daphine Terra floor lamp and Leila crossbody bag

Aram + Ally Capellino: What does the word ‘classic’ mean to you within your world as an interior designer?

Max: A classic, to me, is something that just reads perfectly the first time you see it. So, whether that’s a piece of furniture or a space, things that just click as soon as you see them. I think these can be different things to different people, but there’s also a collective classic.

A+AC: Who or what are your ultimate ‘classic’ designers, movements or pieces?

Max: Top three designers - Gae Aulenti, Carlo Forcolini and Wolfgang Lauberscheimer. I’d probably put Eileen Gray in there as well, just as an extra.

SOMA Soho by Max Radford in collaboration with Cake Architecture

A+AC: Your background is in fine art and antiques. How has your introduction into early-twentieth century design influenced your personal design language?

Max: My in-depth discovery of twentieth century design was done in copy of an old boss of mine’s study of antiques, so quite an analytical look at furniture itself - how the decades relate to each other, and their progression through design. That has been my own insight. But also in terms of the eclecticism that you get in both antiques and fine art; that is something that I look for in my own practice as an interior designer, and also as a gallerist.

A+AC: What is the value of having a strong background knowledge of the ‘classics’ when pushing the boundaries of interior design?

Max: It’s very important to know what’s gone before you in terms of what works and what doesn’t work, what can be relooked at and reinvestigated and what is still to be done. You sort of need to know what’s gone before you to know what you can do next, in some ways. I think people are very good at designing outside of that and just getting on with things obliviously - for example, how outsider art and design will always lead to something new and unexpected - but there’s also an approach to knowing what’s gone before you, which is interesting for the artist or designer because the research part is just as nice as the designing.

SOMA Soho by Max Radford in collaboration with Cake Architecture

A+AC: Speaking of research, what are your current research and referencing methods?

Max: My main research and referencing method is still just buying a lot of books. I swapped buying records for books and spent the same monthly allowance on second hand books. I never like to buy a book for more than twenty quid really - I’ve bought a lot of duds in the years that I’ve been doing it, but I’ve also found a lot of good stuff. So, just continuing to do that. And then there are some amazing online archives that I didn’t know existed until recently, so I don’t always need to buy the books anymore. But yes, just going through things that you can’t access any other way; that seems to be the only way you find the gems.

Recent shows at The Radford Gallery

A+AC: You touched on this already, but how do you approach discovering new or future ‘classics’ as a gallerist?

Max: To discover current designers who are doing amazing work - a lot of it is through the internet, but mainly through social media and Instagram because everyone’s putting their stuff on there in a very good way. Graduate shows are also a very good way to look for new things. Obviously, there are a lot of design galleries internationally so you can see what’s going on through them, but now (even since the last design week) there are lots more London galleries showing young and upcoming designers, so you are able to find new work by looking at other galleries on the London scene which is really lovely as well.

And then you’re just looking for whether you like something immediately or not. When I used to work in antiques, a guy I used to work with - John Corbett - told me you can’t sell anyone anything you don’t truly love and I think I have taken that on in terms of running a design gallery. If you don’t really like things immediately, you’re never really going to show it to someone else and get that passion out of them. So, as long as you really like the stuff, that’s the way of choosing the next classics - you’ve just got to be sure in yourself!

Max Radford with the Zanotta Maggiolina armchair, Lumina Daphine Terra floor lamp and Leila crossbody bag

A+AC: Lastly, how do Ally Capellino and Aram tie in with your personal concept of ‘classic’?

Max: Both Ally Capellino and Aram are London design classics in different ways, so it’s interesting to see them come together. Funnily enough, I have probably known about both of them for the same amount of time. Ally is doing it in a contemporary fashion and Aram, whose founder historically bought contemporary furniture in a contemporary way, is safeguarding it. That, alongside Ally showing timeless designs, is a pretty good combination.

Max Radford

The Radford Gallery

Classic Cuts Part One: Maya Njie

Maya Njie with the Cab armchair by Mario Bellini from Cassina and Ally Capellino Jago Bowler bag

Aram + Ally Capellino: What does the word ‘classic’ mean to you within your world as a perfumer?

Maya: Not having had traditional training in perfumery and being self-taught, I guess I’m learning more about the classics now than I did before. I haven’t come the traditional route and therefore I’m not doing it in the traditional way - but I would say that it’s definitely really inspiring to see how the structures have been laid down and how you can put your own contemporary spin on those.

A+AC: What are your ultimate ‘classic’ scents - not necessarily in a historical sense but rather a personal one?

Maya: In terms of traditional scents, one that I had the opportunity to smell and that really struck a chord with me was the original Eau Sauvage. It’s changed a lot over the years, but the original formula from 1966 by Edmond Roudnitska just reminds me of so many people from my past - not one particular person but more so an era of people. I wasn’t prepared for that and it caught me off guard. I think that’s the beautiful power of perfumery. Then, for me, I tend to work a lot with Virginian cedarwood. I find it really comforting, it reminds me of home. I think that’s a direct link but I also think it’s a really lovely, beautiful material that’s versatile and gender neutral and timeless.

A+AC: Scent and nostalgia are so closely linked. Can you share a personal memory associated with a ‘classic’ scent?

Maya: The one that comes to mind is definitely Tobak. It’s really connected to the interiors of my grandfather’s apartment. I would often go there when I was little - he passed away when I was five, so they’re really early, really positive memories when I think about it. The scent is all about his home, the furniture that he had, him smoking a pipe and having the rolling tobacco mixed in with leather polish, teak furniture and Tonka (represented in the toffees that he would have in a bowl).

A+AC: The scent of leather is firmly associated with furniture and, obviously, leather goods - how do you go about using this ‘classic’ scent in your perfumes?

Maya: Leather, for me, is a really versatile ingredient - and when I say ingredient, I guess I mean a leather accord, because you can’t extract a leather scent as it were. You have perfumers making their own versions of what that could be, so it’s really up for interpretation in so far as how people use it. I find that it works really well across the board. I tend to pair it with florals, with woods, with citruses. Again, it’s a really comforting smell that I guess would be leaning traditionally masculine, but that’s not how I think of perfumes.

A+AC: When do you find value in having a strong background knowledge of the ‘classics’ and when is it more important to be able to use your imagination when pushing the boundaries of perfumery?

Maya: When I formulate, the way that I look at it is a bit like getting dressed in the morning. You look at different ingredients, you look at what would pair well, and you look at classic combinations - but also how you could put two things together that might not be expected. A lot of times, that can lead to a really pleasant surprise for people. I think if you have traditional training, you might be - I don’t know, because I don’t have it - but you might be confined by certain rules and regulations. When you don’t have that, the benefit of is that sometimes you might think out of the box. I guess maybe you learn the hard way sometimes; it’s been a positive thing for me.

A+AC: What are your current research and referencing methods?

Maya: The way I tend to research spans across different areas. So, I like to keep an eye on what’s going on in the perfume industry and then something that I have started doing as well is a retrospective - looking at the perfumes I used to wear in my twenties and thirties to see what the pattern is there, what I’ve gone for, and maybe why I’ve gone for it and whether there’s a connection to how I blend today. I also love reading up about different formulas and methods and I get inspiration and knowledge from all different places.

The Cab armchair by Mario Bellini from Cassina and Ally Capellino Jago Bowler bag

A+AC: Lastly, how do Ally Capellino and Aram tie in with your personal concept of ‘classic’?

Maya: I would say, for me, Ally Capellino is an examplar of how I work in a way. It’s definitely traditional with real contemporary inputs and I feel that it speaks to different generations and genders; it’s not boxed in and it feels quite free. I would say the same about Aram and its history. I feel a connection to Aram - certainly - with my Swedish and Scandinavian heritage and feel like my home has parallels with the furniture that’s sold here.